Season 1, Episode 4 Show Notes:

This week we delve into the deadly Victorian era and Laura tells us about how, if you bought anything green, there’s a good chance it was out to kill you.

Before the end of the 18th century, there was no color fast green, only the option to do a blue overlay with yellow or vice versa. Invented in 1775 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele who, ironically is also credited with discovering oxygen, the artificial colorant was made through a process of heating sodium carbonate, adding arsenious oxide, stirring until the mixture was dissolved, and then adding a copper sulfate to the final solution. A year before the color went into production, he wrote to a friend that he thought users might want to know about its poisonous nature. By mixing arsenic and copper, Scheele developed a pigment that would hold almost no matter what the medium. It also happened to look fantastic under natural and new gas light, an important duality for the time.

Check out the podcast audio to learn a little about arsenic during and after the Industrial Revolution and how this cheap, readily available, poison lead to many unintentional (and intentional) deaths.

As people realized that Scheele’s green was not only cheap but colorfast and able to be applied to a variety of mediums it grew increasingly popular. It made its way onto human bodies in the form of dresses, waistcoats, shoes, gloves, and trousers. It also was found in artificial flowers that were hugely popular for decorating hats, and also, terribly, as a food colorant. Listen to the podcast to learn some of the more tragic stories of people who suffered because of Scheele’s green and the other green dyes that contained arsenic.

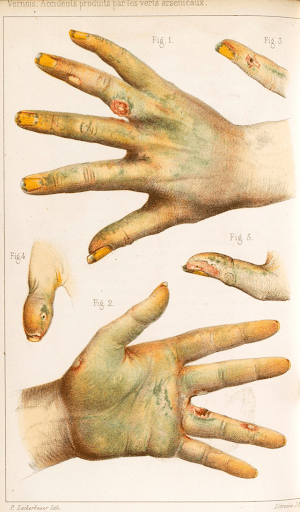

Typically, those who wore green, or worked with it in their daily jobs, but were otherwise healthy were cursed only with a rash or some irritation, maybe the occasional oozing sore. However, many of the arsenic green items that have been tested, along with anecdotes and news stories, show us that many people died from exposure to the green dye during this period.

Green wallpaper was also incredibly popular at the time, especially from William Morris (one of the major figures of the British Arts and Crafts Movement) who loved greens made from arsenic-based dyes. He was highly skeptical of the poisonous nature of arsenic even while he embraced using organic dyes. Unsurprisingly, this was because there was no organic option available to achieve the brilliant, colorfast green he wanted. This effectively rendered the wallpaper people had throughout their homes toxic, particularly in damp environments where the mold caused it to be aerosolized. Here is an example of one of his poisonous and popular – and Caitlin’s all-time favorite wallpaper – patterns:

One of the most prominent controversies that involves Scheele’s green, or more broadly arsenic and arsenic green is Napoleons cause of death. While we explore it more in-depth in the podcast, there are a variety of theories – some debunked – including cancer, murder by his British captors, and long-term arsenic poisoning. Although there seems to be no way to definitively prove that long-term arsenic exposure was his main cause of death, especially with a family history of stomach cancer and a stomach ulcer observed in his postmortem, with testing of his hair and (probable) wallpaper it seems fair to say that his exposure to arsenic almost certainly negatively impacted his health and hastened his demise.

Now that you’ve listened to the podcast and/or read this post…

Check out the picture of Caitlin’s recent antique settee/loveseat purchase below. We need you to vote (below the pic) if you think we should get it tested for arsenic before getting back to restoration. And, on the off chance someone wants to, shoot us an email if you’d like to sponsor this testing.